Autistic sentences, discarded angles

Maybe I'm autistic

No, I’ve not finished my novel. I have been working on it this month — at last! — as the teaching semester draws to a close. More on how that’s going later.

Last year, for the first time in my life, I considered the possibility that I was autistic. The writer Tao Lin, on a podcast, was describing his pattern-spotting instinct, a symptom of his autism. Much to my surprise, behaviours that my parents had enthusiastically egged on as signs of an innate intelligence — remembering car numberplates, observing relationships in numbers, identifying car brands by the sound of their horns — were, in fact, part of Tao Lin’s pattern-spotting trait.

I took a quiz. My answers ranged between “Strongly agree” to “Moderately agree”. When I reached the end I was made to click a big red button to see my results, which then led me to a screen that demanded $100. I never ended up paying, but the range of my answers was telling. I was surely somewhere on the spectrum.

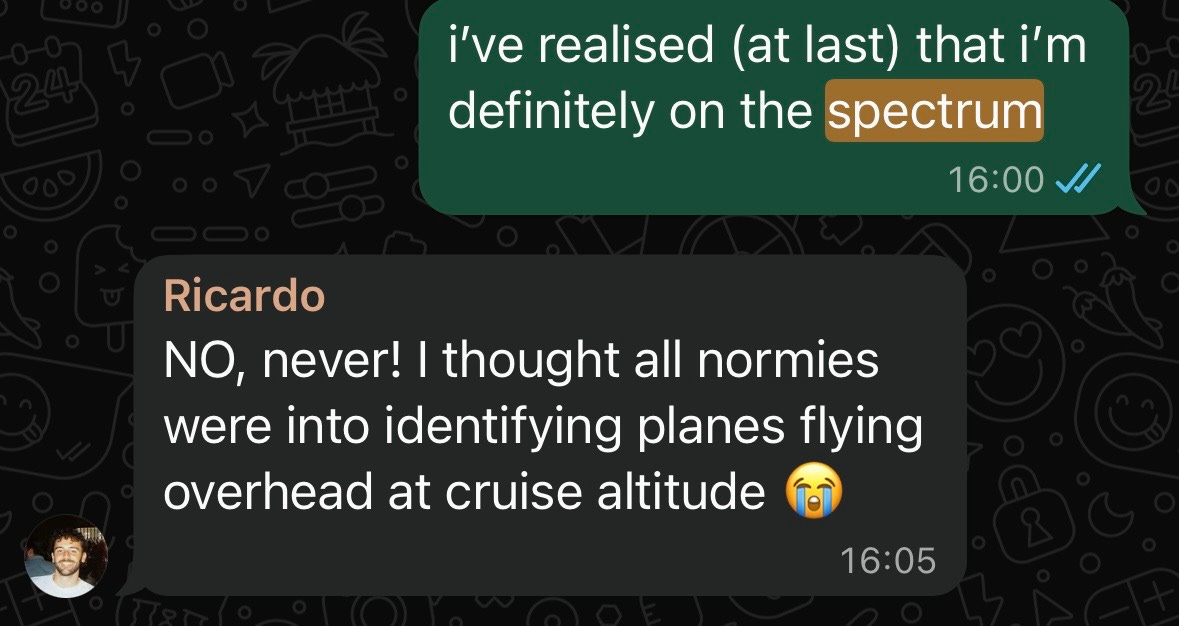

I told Malavika (friend of the show partner of the show) that I thought I might be autistic, to which she said something along the lines of “no shit”. I began to tell my friends of this new suspicion, to be met by anything but shock. This response from Football Manager (autism central)’s Ricardo Domingos (friend of the show) sums it up:

At that point, the novel was very much an autofictional project. I began to think of ways in which I could write this autism situation in. Tonally, the novel was about alienation at work and the anxieties of masculinity — still is in most ways — stylistically, my sentences were veering towards being cold and pared down. This was more of an accident at first, but I gradually began to double down. Gabriel Smith’s Brat was one of my favourite books last year. In an interview he mentions Garielle Lutz’s fantastic lecture The sentence is a lonely place. Reading this sent me down a rabbithole where I began thinking of patterns and rhythm, how one could surprise in a sentence. Then, I encountered Sam Lipsyte’s essay where he mentions the concept of a swerve that the legendary editor Gordon Lish outlines. For Lish, the way to generate rhythm between two sentences is to draw an obvious relationship between them, a sense of similarity, before swerving away. Here are a couple of excerpts from Lipsyte’s essay:

“Let’s look at the beginning of a well-known story from the legendary American writer Barry Hannah, “Even Greenland”:

I was sitting radar. Actually doing nothing.

We had been up to seventy-five thousand to give the afternoon some jazz. I guess we were still in Mexico, coming into Mirimar eventually in the F-14. It doesn’t much matter after you’ve seen the curvature of the earth. For a while, nothing much matters at all. We’d had three sunsets already. I guess it’s what you’d call really living the day.

But then, “John,” said I, “this plane’s on fire.”

“I know it,” he said.

John was sort of short and angry about it.

“You thought of last-minute things any?” said I.

“Yeah. I ran out of a couple of things already. But they were cold, like. They didn’t catch the moment. Bad writing,” said John.

“You had the advantage. You’ve been knowing,” said I.

“Yeah. I was going to get a leap on you. I was going to smoke you. Everything you said, it wasn’t going to be good enough,” said he.

“But it’s not like that,” said I. “Is it?”

The wings were turning red. I guess you’d call it red. It was a shade against dark blue that was mystical flamingo, very spaceylike, like living blood. Was the plane bleeding?”

…….

“But there is something else going on besides acoustical play in Hannah’s passage. My teacher Gordon Lish, who edited Hannah, used to call it the swerve. This swerving, which can also be an amplification, or a reframing, or a negation, creates the strangeness, the newness that cuts against our habits of feeling and perception. It also cuts to the chase. What is sitting radar? Well, it’s actually doing nothing. Then the narrator confesses to not being sure whether they were still in Mexico or not.”

My eyes lit up. What if, to simulate the autistic voice, I played around a bit with the rhythm before delivering a swerve that was not as much of a flourish, not necessarily an amplification, or did not create the wonderful strangeness that it does for Hannah’s writing. In effect, I would emulate the build-up to a swerve in order to deliberately land with something flat. This is not be too dissimilar to how the comedian Stewart Lee writes a joke: an elaborate set up with a punchline that does not always have a conventional payoff (Lee compares himself to jazz music tongue-in-cheek, so this is not dissimilar to jazz I suppose). Long-term Pranavesh Subramanian fans will know that I am well-acquainted (too much, if anything) with the world of stand-up comedy.

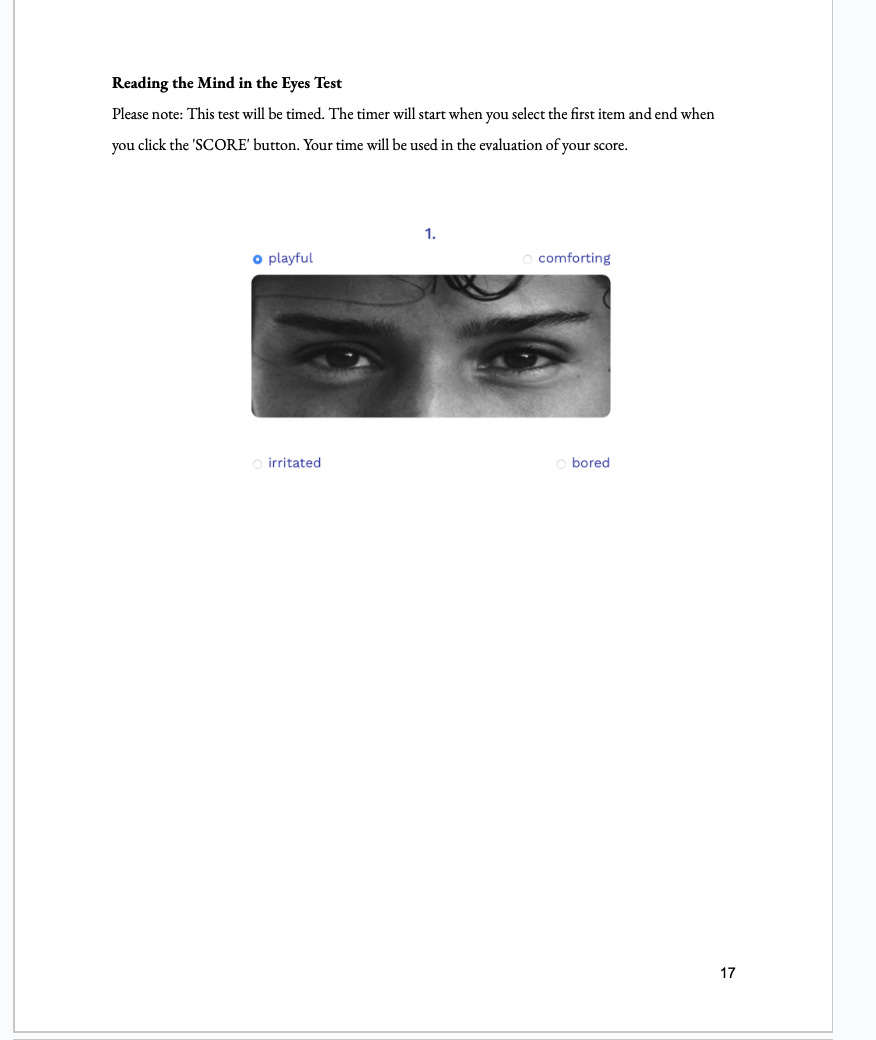

My second angle was to include the entire test in excruciating detail, screenshot by screenshot. 16-pages of screenshots, all 48 questions with my choice indicated on each one of them, ultimately with the payoff that the reader would never know the results, landing on the page that asks them to pay $100 for the screenshot. I have long been fascinated with ‘found’ texts and ways to include them in the novel, the idea of what makes fiction, what makes reality, what is found text and what is generated text, and does it matter that there exist hard boundaries between any.

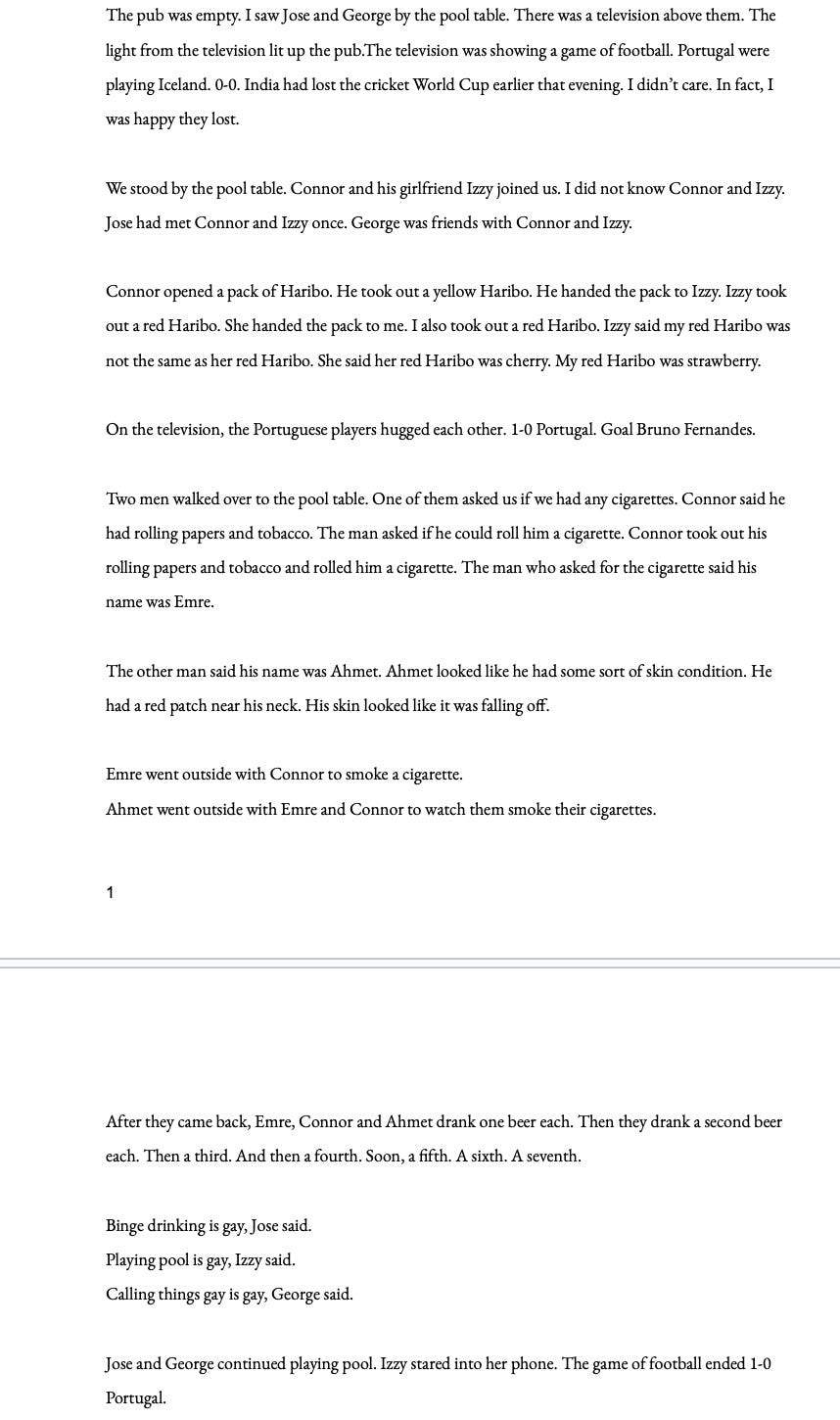

So, around June this year, I had about 30,000 words of a draft that had very short vignettes with sentences that had this flat swerve, making liberal use of found texts. Something like this:

During a workshop in the summer, I was lucky to have Rob Doyle, my actual literary hero, read over my first two chapters along with a group of sharp, enthusiastic writers. While some said the ‘found text’ elements were interesting in the way a work of modern art felt at a museum, the consensus was that it was too long, and happening too often. Rob said something along the lines of making the category error an artist is often susceptible to: in an attempt to convey the affect of alienation, one ends up alienating the reader entirely. My task was cut out: to keep some of these esoteric elements while melding them with more formal conventions that a novel should have, like a plot, or what Martin Amis calls a narrative hook.

By the end of the summer, I was fairly convinced my solution lay in a polyphonic novel — which it still remains — hedging my bets on multiple voices and multiple stories, to paraphrase Amis. But there is more fiction there, that is, more of an arc and more of a voice that is deliberate, invented; more invention in general, of stories, of people, of time and space, of things that happen. There is less auto and more fiction. I wrote about 25,000 words at the end of summer — of this new, second polyphonic voice — which I have in the last few weeks discarded in favour of another voice that I hope serves the novel better. I’m about 3000 words into this one (I have a solid 20,000 words of the other voice that I’m happy with), but for the first time in my writing life, I’m working with an outline and a plan.

The writer Sophie Mackintosh, on her substack, shares the process of writing her drafts, beginning from notes that begin to meander into narrative, to a synopsis, to a draft that grows out of this but the essence of which is to be written as quickly as possible; and then each subsequent draft being edited by hand. I’m attempting to follow this process for the second polyphonic voice, and I’m hoping this bears some fruit this winter.

I still like the autistic voice. I see it in the Booker-winning David Szalay’s work. I read his first, London and the South East late in the summer. That Szalay’s protagonist was a travelling salesman in and around London drew me to the book, (long term Pranavesh Subramanian fans will remember his tech sales job that led him to travel to London frequently some years ago). I loved the book. I have this once every year with a writer, where this slowly morphs into an obsession: I realise we have the same sensibilities, find the same things tickling. Szalay’s prose is anything but minimalist here, but with each passing book, notably All That Man Is, it begins to get increasingly spare, with the occasional flourish, Flesh being the most extreme example of this. This might not be the last time you hear me talk about Szalay.

I’m aiming to write more of this second polyphonic voice (in a Szalayan third person present voice) over the rest of my winter break. I’m excited to place what I have at the end alongside the 20,000 first person words from the other voice, and to see how I can build on that. Maybe 2026 is the year this novel is written. It better be.

Critic-writer Varun Andhare (friend of the show) begins every Substack post with a quip on the weather wherever he is, as a little joke just to amuse himself if not the eagle-eyed reader. I am writing this from my parents’ house in Chennai which is experiencing a ‘cold wave’ — temperatures are a freezing 25 degrees; a welcome respite from Delhi nonetheless.

Here is a picture of a shop I saw in Bangalore which for some reason is called CROYDON, UK. The real question, dearest reader, is if there is a shop on Thornton Way in Croydon called BAIYAPPANAHALLI.

Speak soon xx

Pranavesh

Friend of the show counter

Malavika Madgulkar (mentioned)

Ricardo Domingos (mentioned)

Varun Andhare (mentioned)